The International and Multi-Regional Membership Center of Latinos in the USA

Welcome to you all!

What Is Cinco De Mayo?

PuraVidaCommunity

Cinco de Mayo. a festivity gaining popularity in the southern states, is often

misunderstood by many who celebrate it. Despite the special discounts in national store

chains, local parades, and various celebrations, including those in schools, the true

meaning of this day often eludes people. Many mistakenly believe that 'Cinco de Mayo'

signifies Mexico's independence, a misconception that needs to be clarified.

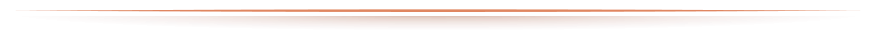

Contrary to popular belief, 'Cinco de Mayo' does not mark Mexico's independence. It is,

in fact, a celebration of the Mexican army's victory over the French army of Napoleon III

in the city of Puebla de Los Angeles in 1862. Led by General Ignacio Zaragoza Seguin,

this victory, known as 'La Batalla de Puebla' (the Battle of Puebla), holds a significant

place in Mexican history.

The historical backdrop of 'La Batalla de Puebla' is crucial to understanding its

significance. Mexico and France had a tumultuous relationship until 1880, marked by

two French interventions. The first, known as the Pastry War (La Guerra de los Pasteles)

in 1838-1839, and the second, the Maximilian Affair from 1861-1867, set the stage for the

Battle of Puebla.

The Pastry War

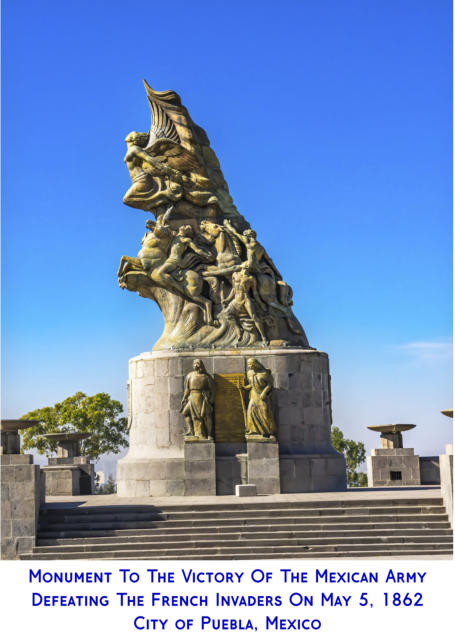

The Pastry War (Spanish: Guerra de los pasteles, French: Guerre des Pâtisseries), also

known as the First French intervention in Mexico or the First Franco-Mexican War

(1838–1839), began in November 1838 with the naval blockade of some Mexican ports

and the capture of the fortress of San Juan de Ulúa in Veracruz by French forces sent by

King Louis-Philippe. It ended several months later, in March 1839, with a British-

brokered peace. The intervention followed many claims by French nationals of losses

due to unrest in Mexico.

This incident was the

first and lesser of Mexico's two 19th-century wars with France, followed by the

French invasion of 1861–67, which supported the short reign of Emperor Maximilian

I of Mexico, who was executed by firing squad at the end of said conflict.

During the early years of the new Mexican republic, there was widespread civil

disorder as factions competed to control the country. The fighting often resulted in

the destruction or looting of private property. Average citizens had few options for

claiming compensation as they had no representatives to speak on their behalf.

Foreigners whose property was damaged or destroyed by rioters or

bandits could not obtain payment from the Mexican government. They

began to appeal to their governments for help and compensation.

Commercial relationships between France and Mexico existed before

France recognized Mexico's independence in 1830. After the establishment

of diplomatic relationships, France rapidly became Mexico's third-largest

trade partner. However, France had yet to secure trade agreements similar

to those that the United States and England (then Mexico's two largest

trade partners) had, and as a result, French goods were subject to higher

taxes.

The Conflict

French troops under Prince de Joinville attacked General Arista's residence

in Veracruz in 1838. In a complaint to King Louis-Philippe, a French pastry

chef known as Monsieur Remontel claimed that in 1832, Mexican officers

looted his shop in Tacubaya (then a town on the outskirts of Mexico City);

he demanded 60,000 pesos as reparations for the damage (the shop's

value was less than 1,000 pesos).

Given Remontel's (which gave its name to the ensuing conflict) and other complaints from French nationals (among them the looting in 1828 French

shops at the Parian market and the execution in 1837 of a French citizen accused of piracy) in 1838, prime minister Louis-Mathieu Molé demanded

from Mexico the payment of 600,000 pesos (3 million Francs) in damages, an enormous sum for the time when the typical daily wage in Mexico City

was about one peso (8 Mexican reals).

When President Anastasio Bustamante made no payment, the King of France ordered a fleet under Rear Admiral Charles Baudin to declare and carry

out a blockade of all Mexican ports on the Atlantic coast from Yucatán to the Rio Grande to bombard the Mexican fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, and

to seize the city of Veracruz, which was the most important port on the Gulf coast. French forces captured Veracruz by December 1838, and Mexico

declared war on France.

With trade cut off, the Mexicans began smuggling imports via Corpus Christi, the Republic of Texas, and into Mexico. Fearing that France would

blockade the Republic's ports as well, a battalion of Texan forces began patrolling Corpus Christi Bay to stop Mexican smugglers. One smuggling

party abandoned their cargo of about a hundred barrels of flour on the beach at the mouth of the bay, thus giving Flour Bluff its name. The United

States, ever watchful of its relations with Mexico, sent the schooner Woodbury to help the French in their

blockade.

Meanwhile, acting without explicit government authority, Antonio López de Santa Anna, known for his

military leadership, came out of retirement from his hacienda near Xalapa and surveyed the defenses of

Veracruz. He offered his services to the government, which ordered him to fight the French by any means

necessary. He led Mexican forces against the French. In a skirmish with the rear guard of the French, Santa

Anna was wounded in the leg by French grapeshot. His leg was amputated and buried with full military

honors. Exploiting his wounds with eloquent propaganda, Santa Anna catapulted back to power.

The French forces withdrew on 9 March 1839 after a peace treaty was signed. As part of the treaty, the

Mexican government agreed to pay 600,000 pesos for damages to French citizens, while France received

promises for future trade commitments in place of war indemnities. However, the Mexican government

did not pay the amount, and France used it as one of the justifications for the second French intervention in

Mexico in 1861.

Following the Mexican victory in 1867 and the collapse of the second French empire in 1870, Mexico and

France would not resume diplomatic relationships until 1880 when both countries left behind claims

related to the wars.

The Maximilian Affair

Maximilian I

Born: July 6, 1832, Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna, Austria

Died: June 19, 1867, Santiago de Querétaro, Mexico

Maximilian was the only monarch of the Second Mexican Empire. He was a younger brother of the Austrian emperor Francis Joseph I. After a

distinguished career in the Austrian Navy; he accepted an offer from Napoleon III of France to rule Mexico.

The second French intervention in Mexico (Spanish: Segunda intervención francesa en México), also known as the Maximilian Affair, Mexican

Adventure, the War of the French Intervention, the Franco-Mexican War, or the Second Franco-Mexican War, was an invasion of Mexico in late 1861

by the Second French Empire, initially supported by the United Kingdom and Spain. It followed President Benito Juárez's suspension of interest

payments to foreign countries on July 17, 1861, which angered these three major creditors of Mexico.

Emperor Napoleon III of France was the instigator, justifying military intervention by claiming a broad foreign policy of commitment to free trade. For

him, a friendly government in Mexico would ensure European access to Latin American markets. Napoleon also wanted the silver that could be mined

in Mexico to finance his empire. Napoleon built a coalition with Spain and Britain while the U.S. was deeply engaged in its civil war.

The three European powers signed the Treaty of London on October 31, 1861, to unite their efforts to receive payments from Mexico. On December

8, the Spanish fleet and troops arrived at Mexico's main port, Veracruz. When the British and Spanish discovered France planned to seize all of

Mexico, they quickly withdrew from the coalition.

The subsequent French invasion resulted in the Second Mexican Empire.[a]

In Mexico, the Roman Catholic clergy supported the French-imposed empire,

many conservative elements of the upper class, and some indigenous

communities; the presidential terms of Benito Juárez (1858–71) were

interrupted by the rule of the Habsburg monarchy in Mexico (1864–67).

Conservatives, and many in the Mexican nobility, tried to revive the

monarchical form of government (see: First Mexican Empire) when they

helped to bring an archduke from the Royal House of Austria, Maximilian

Ferdinand, or Maximilian I. France had various interests in this Mexican affair,

such as seeking reconciliation with Austria, being defeated during the Franco-

Austrian War of 1859, counterbalancing the growing American Protestant

power by developing a powerful Catholic neighboring empire, and exploiting

the rich mines northwest of the country.

After heavy guerrilla resistance led by Juárez, which continued even after the

capital had fallen in 1863, the French eventually withdrew from Mexico, and

Maximilian I was executed in 1867.

1862: French Invasion

The British, Spanish, and French fleets arrived at Veracruz between 8 and 17 December 1861, intending to pressure the Mexicans into settling their

debts. The Spanish fleet seized San Juan de Ulúa and, subsequently, the capital Veracruz on 17 December. The European forces advanced to Orizaba,

Cordoba, and Tehuacán, as they had agreed in the Convention of Soledad. The city of Campeche surrendered to the French fleet on 27 February 1862,

and a French army commanded by General Lorencez arrived on 5 March. When the Spanish and British realized the French ambition was to conquer

Mexico, they withdrew their forces on 9 April, and their troops left on 24 April. In May, the French man-of-war Bayonnaise blockaded Mazatlán for a

few days.

Mexican forces commanded by General Ignacio Zaragoza defeated the French army in the Battle of Puebla on 5 May 1862. On 14 June, the French at

Orizaba, Veracruz, contained the pursuing Mexican army. More French troops arrived on 21 September, and General Bazaine arrived with French

reinforcements on 16 October. The French occupied the port of Tampico on 23 October and, unopposed by Mexican forces, took control of Xalapa,

Veracruz, on 12 December.

Mexico - France in Present Day Diplomatic Relations

In December 2005, a French citizen called Florence Cassez was arrested in Mexico and charged with kidnapping, organized crime, and possessing

firearms. She was found guilty by a Mexican court and sentenced to 60 years imprisonment. Cassez always maintained her innocence, which led to a

diplomatic dispute between Mexico and France. At the time, President Nicolas Sarkozy asked the Mexican government to allow Cassez to serve her

sentence in France. However, the requests were denied.

In 2009, Mexico canceled its participation in 2011 "The Year of Mexico in France" (350 events, films, and symposium planned) as French President

Sarkozy declared that this year-long event would be dedicated to Cassez, and each event would have some remembrance of the Frenchwoman. In

January 2013, the Mexican Supreme Court ordered her release, and Cassez was flown immediately back to France. Since her release, France pledged

to assist Mexico in creating a Gendarmerie in Mexico at the request of President Enrique Peña Nieto.

State Visits

President François Mitterrand attending the North–South Summit in Cancun along with his Mexican counterpart President José López Portillo, 1981

Presidential Visits From France to Mexico

President Charles de Gaulle (1964)

President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (1979)

President François Mitterrand (1981)

President Jacques Chirac (1998, 2002, 2004)

President Nicolas Sarkozy (2009)

President François Hollande (2012, 2014)

Presidential Visits From Mexico to France

President Adolfo López Mateos (1963)

President Luis Echeverría Álvarez (1973)

President José López Portillo (1980)

President Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado (1985)

President Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1989, 1992)

President Ernesto Zedillo (1997)

President Vicente Fox (2001, May and November 2002, 2003)

President Felipe Calderón (2007, 2011)

President Enrique Peña Nieto (July and November 2015)

Historic Border Disputes

France and Mexico do not presently share a land border, although in the 18th-century French Louisiana did border New Spain.

The closest land to the French Pacific Clipperton Island is Mexico, and the two countries disputed the island's ownership for several decades, until

international arbitration finally awarded it to France in 1931.

Mexico-France Trade Relations

In 1997, Mexico signed a Free Trade Agreement with the European Union (which includes France). In 2015, two-way trade between France and

Mexico amounted to $5.8 billion USD.[12] Between 1999-2008, French companies invested over $1.7 billion USD in Mexico. At the same time, between

1991-2009, Mexican companies invested $594 million USD in France. France is Mexico's 16th biggest trading partner while Mexico is France's 53rd

biggest trading partner globally.

Resident Diplomatic Missions

France has an embassy in Mexico City.

Mexico has an embassy in Paris and a liaison office in Strasbourg.

If you want to offer us your opinion, click on the button labeled My Opinion. Thank you.

| $thisUseris |

Updated May 1 2024